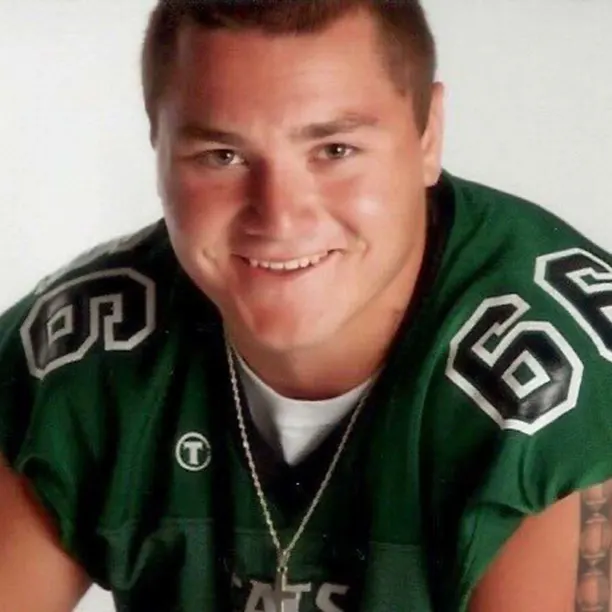

Harrison Phillips: a nurturer by nature

By: Lindsey Young

When 11-year-old Harrison Phillips walked into the middle school lunchroom, he didn't see many empty seats. Harrison had been finishing up a project and arrived late to lunch, meaning the typical table he sat at with his football team was full. As was the wrestling team's table, another place he sometimes found himself.

But then he spotted some vacant seats beside students and teachers from the Special Education department ate their lunches. Harrison strolled over, slid into a seat, smiled and offered a wave to others at the table. In his peripheral vision, he noticed the school's principal headed his direction wearing a ready-to-scold expression.

"He thought I was making a joke or gonna do something inappropriate," Harrison said. "And I just introduced myself and tried to meet the kids where they were."

Young people with developmental differences often fall victim to bullying by their peers or, at the very least, encounter other young people who simply are uncomfortable around those with abilities differing from their own.

.png)

Harrison always has been unique that way, though. His mother, Tammie, previously was a teacher but started an at-home daycare when Harrison was a year old. Hence, he and his sister Delanie grew up with children of all different backgrounds, physical abilities and cognitions.

"They were able to adapt to each of those different kids and knew how much love that we had for them – and [the importance of] inclusiveness," Tammie said. "We played a lot of soccer in the backyard … so just including them. Making sure they were in the game and able to do everything that our kids could do." Tammie noticed her children exhibiting patience and kindness at a remarkably young age.

"It was just a part of their nature – part of being in an environment where there's a lot of kids before and after school and not only did they have to share their toys, but they had to share me, too," she said. "Sometimes that can be hard, but that [didn't seem] hard for them at all."

Harrison and Delanie followed the examples of their parents, who consistently mentored within the school system or served at their church. The Phillips family every December "adopted" a local family experiencing hardships and provided food and gifts for the holidays.

Harrison's Playmakers

For the Phillips kids, the apples didn't fall far from the tree. Delanie volunteers for a suicide text line. And Harrison? Well, giving back has simply become a lifestyle for the defensive tackle. A week doesn't go by without an appearance at a children's hospital, an elementary school or one of his teammate's charity events. It's not uncommon for Harrison to make multiple visits in one week. It seems exhausting, really, for any one person. But it seems to only further fuel Harrison's desire to make a difference.

Harrison spent the first four seasons of his NFL career in Buffalo, where he quickly won over the hearts of Bills Mafia by his ceaseless community work: hosting a kickball game for young athletes with intellectual disabilities, visiting a group of teen girls with cancer for a "Galantine's Day Party" and serving as the Keynote Speaker at the 2020 Special Olympics New York Winter Games. And then of course there's Harrison's Playmakers, his personal foundation that supports children and young adults with developmental differences and special needs.

Paul Spinelli/AP

Paul Spinelli/AP

Tight end Dawson Knox joined the Bills as a third-round draft pick in 2019 and immediately noticed the impact Harrison made on the locker room. "I first thought he was an offensive lineman. You can't tell which position he's in based on who he hangs out with because he's always hanging out with everybody on the team," Knox told Vikings.com. "From DBs to receivers, he's friends with the whole team. It was fun coming in and getting to know him, just because it was so apparent that everybody on the team already liked him so much.

"He was a leader. There's no question that he was one of the guys that everyone kind of looked up to from the get-go, and he was only in his second year at the time," Knox continued. "It was just really impressive to see the way he could juggle everything with football but then all he did off the field, too."

Harrison's foundation first was inspired by the Playmakers organization, which provided after-school literacy programs in at-risk school districts. Having graduated from Stanford with a minor in education, Harrison initially dived into the Playmakers work, even starting a similar program in Omaha.

"But that wasn't exactly where my calling was," he said. "My first year in Buffalo, I would go speak to an inner-city classroom, and I'd go with my teammate who looked more similar to them and had a more similar background compared to "Omaha, Nebraska-Stanford-white guy." They couldn't relate to my story as well. So I transitioned in Buffalo when I saw [another] area of need. … That's where I really split off and started doing my own thing."

The defensive tackle began hosting "Harrison's Sports Camps," intentionally leaving football out the name because the programming reaches far behind Harrison's sport of choice. His camps include a basketball station, a soccer station and drill stations for various football positions. But the camps are about much more than athletic prowess.

"You might go play soccer and then your next station is a petting zoo – and we have goats and donkeys and bunny rabbits. And then you go to basketball, and then your next station is face painting," Harrison explained. "And then you have the quarterback station, and then the next one is we have this huge, inflatable bounce-house obstacle course.

"It's not all work. It's work and play," he added. "Sports are so great for proving this independence, right? Failing and getting back. Shooting nine shots, missing all nine, but believing in yourself that you're gonna make the 10th one."

Just like playing backyard soccer with his mom's daycare kids, Harrison – a two-time Walter Payton NFL Man of the Year nominee – makes sure no camper is ever left out, regardless of physical or cognitive ability.

As you can imagine, it's not easy for a 6-foot-3, 300-pound individual to go through an inflatable obstacle course meant for kids, but Harrison has carried children with Spina Bifida through the colorful gauntlet. He's helped create unique basketball drills to allow blind children to participate. The camps include numerous children with Down's Syndrome or who are on the autism spectrum, and Harrison and his staff work to "meet them where they're at."

Harrison's Playmakers camps are free – and often include complimentary food, goodie bags and other swag – but incorporate a pay-it-forward element. "Maybe I'll find an animal rescue here and find out what they need and say, 'Hey, Playmakers, as you guys come to the event, bring one of these items to drop off to a local animal rescue.' Or to help our vets. 'This is what the VA needs right now.'

"You talk about my camp that has 500 kids at it, over half of them are bringing something – well, now we've got 10-thousand-plus dollars of donations to an animal shelter or different organization," Harrison added. "That's what Harrison's Playmakers is all about." Harrison often invites teammates to help operate his camps, as well.

"I went to one of his camps that we had at the Bills stadium, which was awesome. It was so fun being able to kind of hang out with some of those kids and throw the football around, crack some jokes," Knox said. "Just to see him in his element was pretty awesome. It was pretty apparent how the kids felt like he was one of their friends. They just kind of gravitated toward him. He was very natural."

Early and often

Tammie Phillips believed for years her son would make it to the NFL. She also knew he'd make a difference when he got there. When Harrison was in fifth grade, she said, he handed Tammie three pieces of white paper and asked her to draw a large letter on each sheet.

" 'Well, sure. What do you want me to put on them?' And he said, 'I want an F, I want an N and I want an L – big.' And I'm like, 'Oh, OK.' So I put these three letters on three separate pieces of paper, not knowing what they spelled in the moment," Tammie recalled. "He takes them and puts them above his bed and spelled NFL. So every night, he'd look at those [and] right then, I just knew, 'Oh my gosh. This kid is just going to exceed anything we thought was possible.' "

Harrison kept his eyes on the goal and fulfilled his childhood dream of making it to the NFL. But along the way, giving back always came first. Around the time he taped up the N-F-L, Harrison also met a couple of neighborhood kids with developmental disabilities and became fast friends, despite the difference in cognitive function. He regularly rode his bike over and asked parents if he could play basketball with their sons. And as a senior in high school, he invited multiple students from the special education program with him to prom. Harrison, the popular football player, was crowned Prom King.

It sounds like a feel-good teen flick starring Chad Michael Murray; but for Harrison, it's just everyday life. (It's worth noting that Harrison has developed a friendship with Murray – but that's another story for another day.) He's one of the most selfless people you'll meet, to be sure – but he also is so thankful for the return on his investment.

"With the NFL being such a roller-coaster of the highest highs and lowest lows, something that's always been a constant for me is the relationship I have with the kids and young adults I work with," Harrison said. In Week 2 of the 2019 season, Phillips recorded three tackles against the Giants and split a sack-fumble of Eli Manning with Lorenzo Alexander to help Buffalo to a 28-14 win. The very following week, Harrison suffered a torn ACL against the Bengals, sidelining him for the rest of the season. A Monday MRI confirmed the ACL tear. On Tuesday, Harrison spent the morning at the local children's hospital.

"I was in such a low place, but I know this is a place where I'm going to be loved. They don't care [if I'm injured]. They love me," Phillips said. "When I'm at the top of the mountain or the bottom of the valley, my relationships through my foundation – they love you regardless. "Some of the kids I work with, they're going through way worse battles than what I'm going through, and it's just a great reminder to have better perspective on life," he added.

New home, new opportunity

New home, new opportunity

Harrison planned community events in Minnesota practice before ink dried on his contract with the Vikings. Since arriving in Minnesota for spring workouts in April, Harrison has visited the M Health Fairview University of Minnesota Masonic Children's Hospital and Children's Minnesota, spending time with young people battling cancer and other difficult conditions. He also learned about All Square, a social justice-focused program close to Eric Kendricks' heart, and hung out with youth at the Little Earth Boys & Girls Club.

He spent a sunny afternoon – along with Viktor the Viking – at Crescent Cove, one of only three respite homes for children in the country. Whether holding the tiny hand of 2-year-old Matilda or visiting with 20-year-old Mari about their shared affinity for Eminem, Harrison simply was present.

Last month, Harrison invited new Vikings teammate Kenny Willekes to Falcon Ridge Middle School for a "Best Buddies" event with youth who are part of the school's special education program. He laughed and told stories with students, took on a couple young men in hoops and initiated a game of Duck, Duck, Goose … which he quickly learned is called Duck, Duck, Gray Duck in Minnesota. "My mother always told me, 'To whom much is given, much is expected,' " Willekes said. "It's always felt important to give back, and Harrison's provided me with the opportunity to do that.

"My first couple years I haven't had a lot of opportunities [due to COVID-19]," Willekes added. "Harrison's been here for a week, and he's been to multiple events. Being able to work with him and see his example of how to be a leader on and off the field, he's made a huge impact already."

Courtesy of Minnesota Vikings

Courtesy of Minnesota Vikings

Katey DeMarais, State Director at Best Buddies Minnesota, explained the impact Harrison's involvement can have on the young people. "At Best Buddies we are working hard to make sure that individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities belong in our schools, communities and workplaces," DeMarais said. "So to have Harrison bring his passion for inclusion to Minnesota is really exciting – not only for Best Buddies but for the [entire] disability community.

"Everyone was so excited for the visit, and it was an amazing day," DeMarais continued. "It was really cool to see that Harrison and Kenny were so genuinely excited to interact with and celebrate our buddies, who are so often left out and left behind. It helps bring to light our mission that people with disabilities should be included no matter what."

Harrison's motor for good is nonstop. When Knox heard that Harrison hasn't wasted any time diving into his new community, he said he wouldn't expect any less from his former teammate. "I'd be surprised if he hadn't done it already," Knox said. "But that's incredible. That's just Harry."

Courtesy of Minnesota Vikings

Courtesy of Minnesota Vikings

Tammie just offered a warm-hearted laugh and echoed Knox's sentiments. "That's Harrison," she said. "We did tell him, 'This is a whole new chapter for you now.' So before he left to go up to Minneapolis, we're like, 'You know, take your time. You've got to learn all your coaches' names; you've got to learn all your teammates' names; you've got a whole new routine for everything – the workouts, the playbook. Take your time merging into the community.'

"That is exactly what Paul and I said,' " she added. "Obviously he did not listen to us, but nobody's upset about that. … We're very proud." It often seems like just yesterday that Tammie told Harrison as an eighth-grader to watch out for younger students.

"We told him, 'You know, there's going to be a sixth-grader coming in that's gonna be nervous, going to be scared, and we want you to help pull them along and help them get comfortable with their new school,' " Tammie said. "We've always wanted him to reach back and help the next person, or pull up the next person. That is very important to us. And no matter what, you need to always give back. … We want him to always, 'See where you came from and see where you've been, and that will help you even more in the future.'

"He's a wonderful kid. Well, I can't call him a kid anymore," Tammie chuckled. "We just look forward to the future to see not only what he does with football but what he can do in the community."

Unlabeled photos Courtesy of Harrison and Tammie Phillips